Lori Daniels and a team of researchers plan to let a hand-held GPS guide them in a few weeks to more than 100 spots in the charred forest around Jasper, Alta.

At each location, they'll plunge a stake into the ground and take notes. Are there needles left on the trees? The branches? How far up is the tree charred? Are roots exposed?

In fewer words, they'll be asking: how bad was the fire?

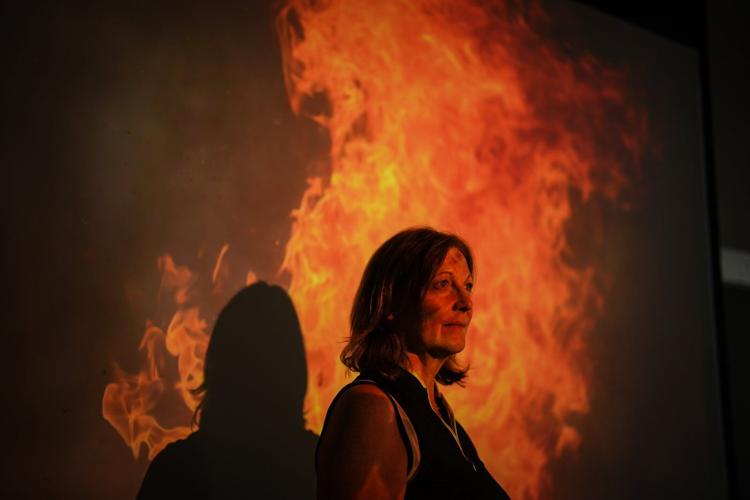

Daniels, who has been back to Jasper several times since last summer's destructive fire, says she has partly observed the answer to that question.

"I've seen a lot of devastating fires across British Columbia in the last decade. I've spent a lot of time in burnt forest," said Daniels, a professor and co-director at the University of British Columbia's Centre for Wildfire Coexistence.

"And I have to say, there are parts of the Jasper fire that were absolutely shocking."

It has been nearly a year since wind-whipped wildfires burned a third of Jasper's structures to the ground.

Outside the town's limits, what happened in the nearly 330 square kilometres of singed forest has interested researchers. They want to know whether more than 20 years of forest management affected the fire's behaviour as it barrelled toward the townsite — and whether there was a fire tornado during the blaze.

Parks Canada had done extensive work to thin the overgrown forest surrounding the town during that two-decade period, said Daniels, who had several research plots in the area years before the fire. She said she believes much of Jasper is still standing because of Parks Canada's efforts, including prescribed burns and trimming trees.

´şÉ«Ö±˛Ą forest agencies are still trying to figure out the best ways to treat their forests so that a wildfire can be slowed down before it reaches a community, Daniels said. The upcoming research could help Parks Canada and provincial wildfire agencies figure out whether treated parts of the forest helped firefighters protect neighbourhoods.

"(It's) a really critical question. The treatments cost thousands of dollars per hectare, tens of thousands in some environments," she said. Insured damages from the fire have been estimated at about $880 million.

Parks Canada is supporting Daniels' research. It's also undertaking a "series of investigations and reviews related to the fire," it said in a June statement.Â

Laura Chasmer, an assistant professor at the University of Lethbridge, had 34 research plots in Jasper before last summer, 19 of which were burned in the fire. She and a group of students are continuing previous research on the type of fuels that build up in forests and can make wildfires more vicious.

Part of that research has sought to understand how peatlands and trees killed by pine beetle can contribute to the spread of wildfire.

"Climate change is changing forests in ways that we really don't understand," Chasmer said.Â

One of Chasmer's students will be joining Daniels this month when the research begins around Jasper.

"It was really hard for us to go back there," Chasmer said of Jasper, where she has conducted field research since 2021. "But I think that we can learn so much from this fire."

Whether there was a tornado during the fire has also intrigued researchers from around the country. Mike Flannigan, research chair at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, B.C., has publicly suspected a fire-induced tornado happened during the Jasper blaze.

"It sure sounds and looks like it was a tornado," he said.

Researchers from Western University's Northern Tornadoes Project in London, Ont., are trying to confirm precisely what happened in the Jasper inferno.

Aaron Lawrence Jaffe said there are suspicions of the rare phenomenon.

Huge swaths of thousands of trees were uprooted or snapped, said the engineering researcher for the project. And debris, including a shipping container, several heavy-duty metal garbage bins and heavy campfire pits, were flung hundreds of metres from their original spots.

"It was unlike any wind-damage survey I've done before," Jaffe said. "There's evidence that there was some kind of vortex."

The kind of damage witnessed could have only been created by winds of about 180 kilometres per hour, he said.

His team also took drone photos and videos of the damage to help find potential patterns that could have been caused by a twister.

However, he said, fire tornadoes are a nascent field of research as very few have been recorded worldwide. The lack of radar coverage in Jasper is also a complicating factor for researchers, making it difficult to determine whether there was a tornado.

They're also awaiting data from federal researchers, which would help determine if there was fire-induced weather that could generate a tornado.

Jaffe said he hopes his lab will have an official answer in the coming months.

This report by ´şÉ«Ö±˛Ąwas first published July 21, 2025.