SAN ANTONIO (AP) — Irma Reyes changed clothes in the back seat of the pickup: skirt, tights, turtleneck, leather jacket. All black. She brushed her hair and pulled on heels as her husband drove their Chevy through predawn darkness toward a courthouse hundreds of miles from home.

She wanted to look confident — poised but hellbent. The outfit was meant to let Texas prosecutors know just what kind of formidable mother they’d be crossing that morning.

Weeks earlier, Reyes learned about the plea deal. State lawyers planned to let the two men charged with sex trafficking her daughter walk free.

She’d barely been able to eat or brush her teeth since, her mind racing: Why are they doing this? Can I get the judge to stop it? Don’t they know my daughter matters?

Reyes' daughter was 16 in 2017, when men she knew only as “Rocky” and “Blue” kept her and another girl at a San Antonio motel where men paid to have sex with them. Now, the cases against Rakim Sharkey and Elijah Teel — the men police identified as the traffickers — have seen years of delay, a parade of prosecutors, an aborted trial and, ultimately, a stark retreat by the government.

They are among thousands of cases under a at the office of Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, who has risen to national prominence fighting court battles that affect people nationwide even while facing legal troubles including a by officials. Trafficking cases in particular have cast doubt on how the agency uses millions of state tax dollars on an issue that Republican leaders trumpet as a priority while attacking Democrats’ approach to border security.

For Reyes, her daughter, and other victims and families, the politics take a backseat to their pain. To them, the plea deal is a case study in how the agency's troubles are undercutting justice for vulnerable victims.

A spokeswoman for the attorney general’s office, Kristen House, declined to answer questions about the deal, the actions of prosecutors, and other details of the case involving Reyes' daughter.

“It’s like a nightmare that I can’t wake up from,” Reyes told The Associated Press.

______

The case was ready for trial years before that January day Reyes and her husband made their way to the San Antonio courthouse, said Kirsta Leeburg Melton.

“You will not find a stronger corroborated case,” said Melton, who oversaw the attorney general’s human trafficking unit until late 2019 and now runs the Institute to Combat Trafficking. “And I’m sick. It’s wrong.”

In the courthouse, Reyes’ stomach churned as she thought of the deal for the two men: five years of probation. The original charges carried potential sentences of decades in prison.

“I need to puke,” said Reyes, 45, her heels clicking down the hallway to the bathroom.

Inside the crowded courtroom, she waited on a back bench for hours, watching people charged with drug crimes and drunken driving draw harsher sentences.

One of the defendants walked in and sat for a while on the same bench. Just one person separated them, but he seemed not to recognize Reyes. She squeezed her husband’s hand.

When the judge got to their case, she summarized its twists and turns: years lost to the pandemic, delays due to “turnover in the attorney general’s office,” days of testimony last year only for several people to catch COVID-19 and prompt a mistrial.

A defense attorney for Sharkey said his client was in a “strong position” for acquittal but would accept the deal to put the case behind him. Reyes listened in disbelief as the new prosecutor told the judge that Reyes’ daughter — now a 22-year-old with whom she keeps up a steady stream of text messages — was “on the run.”

Sharkey and Teel pleaded “no contest” to aggravated promotion of prostitution. The judge, Velia Meza, sentenced the men to seven years of probation, despite prosecutors recommending five, adding that they’d be strictly supervised but wouldn’t have to register as sex offenders.

Then, it was Reyes’ turn. Meza would allow a victim impact statement.

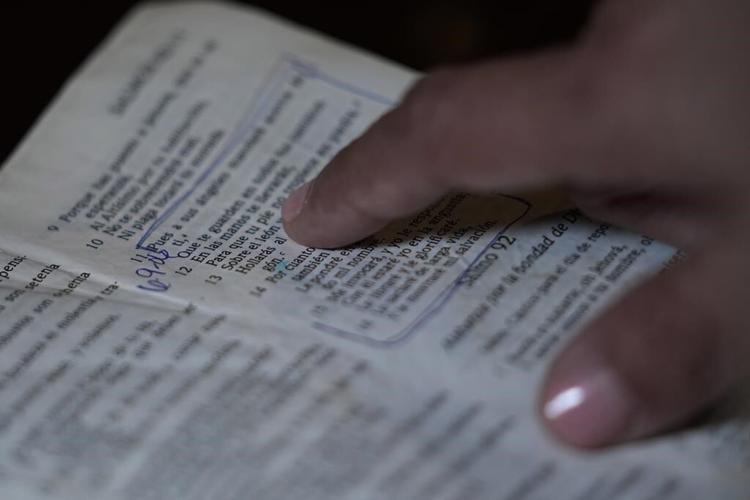

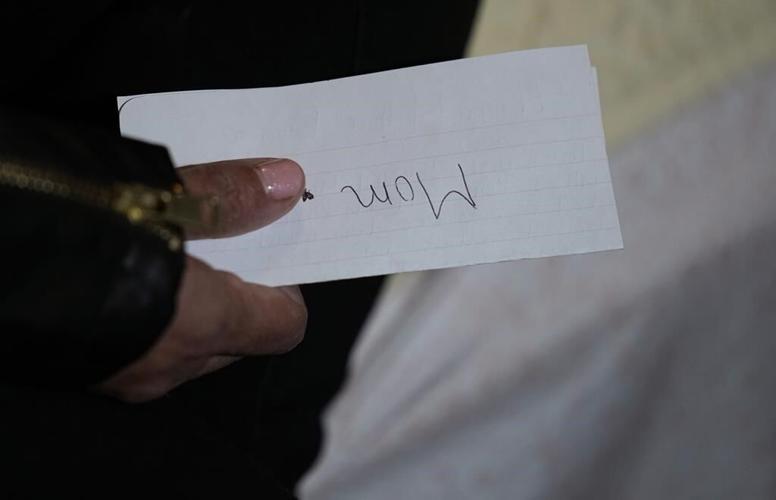

Reyes walked slowly to the front of the court, clutching her handwritten statement. She thought of her daughter: a beautiful soul who blasts Beyoncé and loves her dogs, a fighter who overcame a lifetime of struggles to get sober, a woman who took the witness stand just months earlier against the man charged with trafficking her.

Reyes reached the waiting bailiff. She took the microphone.

____

Reyes’ daughter lost a brother when she was young. Then her estranged father died. She was bullied at school.

The AP is withholding the young woman’s name, in keeping with its policy to avoid identifying victims of sexual assault and other such crimes. Reyes told AP she spoke about this story with her daughter, who did not want to comment or be interviewed directly.

Reyes said that as a girl, her daughter would run away from the large family’s South Texas home. By her teens, she started using drugs and getting psychological care through the juvenile justice system. In September 2017, she was sent to a rehabilitation center.

Court records show it was only days after Reyes’ daughter and another girl ran away from rehab that their photos were advertised online for “dates” out of a motel room off the interstate. They met “Blue” outside a motel, where they couldn't afford a night's stay. He introduced them to “Rocky.” The pair rented the girls a room, helped set up meetings with men who’d pay for sex, and collected half the money at the end of each day, according to the records.

Reyes’ daughter later testified that when one of the men hit her, she got scared and called her mom. Reyes found the phone number advertised on Backpages, a classifieds website later shut down by law enforcement. She called police; officers found the girls at the motel that night.

Ten days after running away, Reyes’ daughter was in a juvenile lockup talking to a detective who would spend months tracking down the men.

“We’re able to get the surveillance video. We were able to get room receipts. We were able to get cellphones, which were extracted for data,” detective Manuel Anguiano told AP. “I don’t think I’ve ever worked a case that had more evidence.”

Several people who worked on the case told AP they were outraged by the attorney general's office's final resolution.

“It’s absolutely an unfortunate outcome,” said Cara Pierce, who oversaw the agency's human trafficking unit until August 2022. “This was a triable case when I left.”

Sharkey’s lawyer, Jason Goss, maintains the jury would have acquitted his client but told AP he had no choice but to plead no contest to the reduced charge because the potential sentence of 25 years to life was too risky. Teel’s attorney, Brian Powers, didn't respond to phone messages and emails seeking comment.

After getting out of the detention facility, Reyes’ daughter lived away from home for a while, then returned to her mother’s house on a quiet, residential block.

She barely left her spartan bedroom, Reyes said, and couldn’t talk about what had happened. Reyes in turn got anxious when her daughter was around men. They avoided crowds.

Reyes coaxed her back into the world. She brought her treats – Flamin’ Hot Cheetos and Limón Lays – and the book “Women Who Run with the Wolves.”

Gradually, they ventured out, taking morning walks in a nature preserve, watching the birds while eating lunch in Reyes’ car. But the young woman still had panic attacks, sometimes shutting herself in the bathroom.

That’s where she was when Connie Spence, a prosecutor who signed on to the case in summer 2020, arrived to talk, Reyes said. Spence got down on the floor, speaking calmly as the young woman hyperventilated.

After that, Reyes said, her daughter began weekly counseling. She started volunteering at a library and museum. She reenrolled in school and, last June, mother and daughter drove together to San Antonio to testify.

“They built a bond somehow,” Reyes said. “Connie gave her hope.”

On the witness stand, Reyes’ daughter struggled to breathe and had difficulty recalling details from years before. But over hours of testimony she recounted how she came to be having sex at the motel to pay "Rocky.” She testified that he got mad after she spoke to other men there, taking her into a room and hitting her across the face.

Asked to identify “Rocky,” the young woman pointed across the courtroom at Sharkey.

___

Four days later, Reyes and her daughter were relaxing in the summer heat on their patio when Spence called to tell them the judge had declared a mistrial because four people in the courtroom caught COVID-19.

They told themselves testifying would be easier the second time. All three women agreed to go back to court as many times as needed.

But it would be the last time they spoke to Spence.

She left the attorney general’s office the following month, according to personnel files obtained under public records laws. Spence’s resignation letter gives no reason. She didn’t respond to calls and messages seeking comment.

Spence left amid a wave of over practices they said were meant to slant legal work, reward loyalists and drum out dissent. The next month, the office dropped a separate series of trafficking and child sexual assault cases after losing track of one of the victims.

In October, Reyes was introduced to new lead lawyer James Winters — the last of eight prosecutors to handle the case for the attorney general's office, court records show. Reyes said her daughter told Winters she would testify again.

The lawyer later asked that the case be postponed again, but the judge refused. Reyes didn’t hear from prosecutors again until early January, when Winters called about the plea deal. It was a couple weeks after her daughter had left home.

In the silence, she’d grown pessimistic about the case. They had a fight, Reyes said. The young woman went to stay with a friend’s family.

Reyes worried about her daughter and whether she might turn to old habits. She spent Christmas with the family, but left soon after.

Still, a victim’s advocate told prosecutors that Reyes could get her daughter to court, internal office messages obtained by AP show. Reyes doesn’t understand why Winters later told the judge her daughter was “on the run.”

Winters, who referred emailed questions to an attorney general's spokesman, submitted his resignation letter three weeks after appearing in court for the plea deal, which was first reported by

___

In San Antonio, Reyes clutched her jacket around her shoulders as she reached the front of the courtroom and took the microphone for her victim impact statement.

She'd spent lunch writing out what she wanted to say, but rage got the better of her planning. She looked at the men accused of trafficking her daughter and two other girls, at the lawyers flanking their clients, at men who'd also gotten probation on charges of soliciting and paying the girls for sex.

Reyes began speaking quietly, the statement still crumpled under her jacket.

“Rakim, can you look at me?” she said, as Sharkey examined his hands. “You have daughters. Going on your third. Exactly the number of victims.”

She told one of the men who'd paid for sex that she's glad his family left him.

And she gestured at Winters, the prosecutor. “He doesn’t represent me. I represent myself right now. I'm not afraid of you.”

Reyes spoke for nearly five minutes, her voice rising as she turned to face the courtroom and beseeched people who were being trafficked to come forward.

“There are victims out there that this minute are being pimped by these types of guys, this type of trash,” she said. “And the trash is supposed to be disposed. But they’re lucky today.”

Reyes' voice broke.

“What these people do to their victims — nothing will ever fix that,” she said. “We just try to hold on.”

___

Reyes cried on the way home, but the drive otherwise passed in silence. Her husband, who doesn’t speak much English, hadn’t followed everything in court. Reyes didn’t know how to explain.

She also didn’t know how to tell her daughter, who'd already lost hope the men would go to prison.

Reyes wanted her to come home, to talk in person. But her daughter’s bedroom was empty.

Reyes felt isolated and got little rest, with violent nightmares. She kept the blinds drawn. She struggled to breathe and fantasized about feeling nothing.

Two days after the hearing, Reyes sat alone in her bedroom, where crosses line the walls. She felt abandoned by the prosecutors, by the judge, by her family, by God. She thought about how she would take her own life. The idea seemed soothing. Her thoughts grew specific. But then she thought of her children and called a crisis hotline.

“I just swim into my thoughts,” she said. “It’s like a big ocean once you let your mind wander. But pulling yourself back up, that’s where I have to be aware that I don’t dive too deep.”

Reyes turned 46 the next week. She spent her birthday at the doctor’s office. She cried uncontrollably. The doctor prescribed anti-anxiety medicine.

Reyes is in therapy. She’s signed up for dance classes and walks her dogs in the nature preserve, hoping her daughter will join them soon.

She's still grasping for closure. Reyes filed complaints with the attorney general’s office, the state bar association and the U.S. Department of Justice, although none will reopen the criminal case. Perhaps her best hope from the legal system is a civil lawsuit that she hopes her daughter will one day be ready to bring.

She and her daughter talk more lately. Their texts are filled with worry but also jokes and photos.

One day, Reyes’ son shook her awake at 3 a.m. A sheriff’s deputy was on the phone and said her daughter had called 911 having a panic attack; she said she wanted to go home.

I’ve lived this before, Reyes thought. She asked the deputy to wait with her daughter.

Then she pulled on shoes, climbed into the pickup and drove out into the night.

____

EDITOR’S NOTE — This story includes discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, please call the ��ɫֱ�� Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.

____

Associated Press photographer Eric Gay and videojournalist Lekan Oyekanmi contributed to this report.